3D Development

My relationship with 3D software and printing is complicated. I’ve always had one foot in and one foot out of the technology that creative world has been in lust with for the last 25 years.

The expectation of every designer using a Wacom tablet and a 3D printer daily has yet to take shape, but the promise is too great to dismiss. The concept of sketch to product is compelling but the realities of product creation, evolving technology and status quo have slowed the future from arrival.

In 1993 I was introduced to 3D software as a co-op student with AT&T in New Jersey. My manager for three amazing semesters, David Britt, was an Australian designer that had a gift for building with his hands. He built an observatory in his backyard instead of a treehouse.

However at work his corporate money fueled his obsession with the 3D printers and software that would fill his 1500 sqft ideation laboratory.

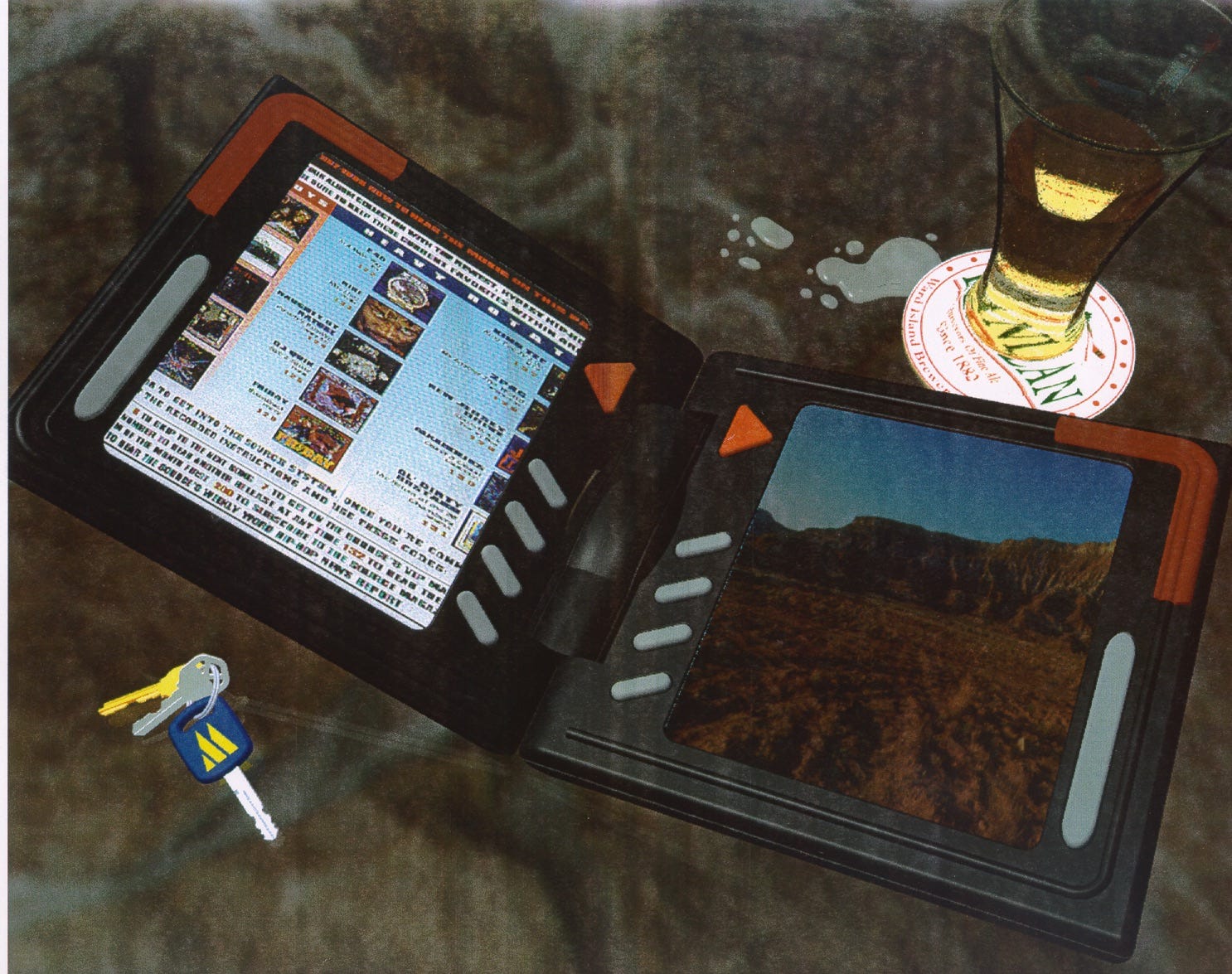

In those days AT&T still developed consumer products and David was in charge of housing the complicated equipment that the electrical engineers would develop with the software engineering team. I couldn’t tell you exactly how the communication devices actually worked but we were supposed to build a protective case that made the technology user friendly.

In Dave’s laboratory we spent very little time sketching. There were no mood boards or consumer imagery to slow us down. There were just two Silicon Graphics workstations and three 3D printers. We were a factory of rectangular plastic boxes that would house wires, batteries and boards. Our renderings were phenomenal and the printouts were lifelike.

The skills I developed at AT&T migrated back to school where I worked in Georgia Tech’s 3D lab with David Rosen and interned with Silicon Graphic’s southeastern sales office as a software jockey for demos. I could model quickly and I had the ability to code switch from software geek to regular business folk.

But I wasn’t designing.

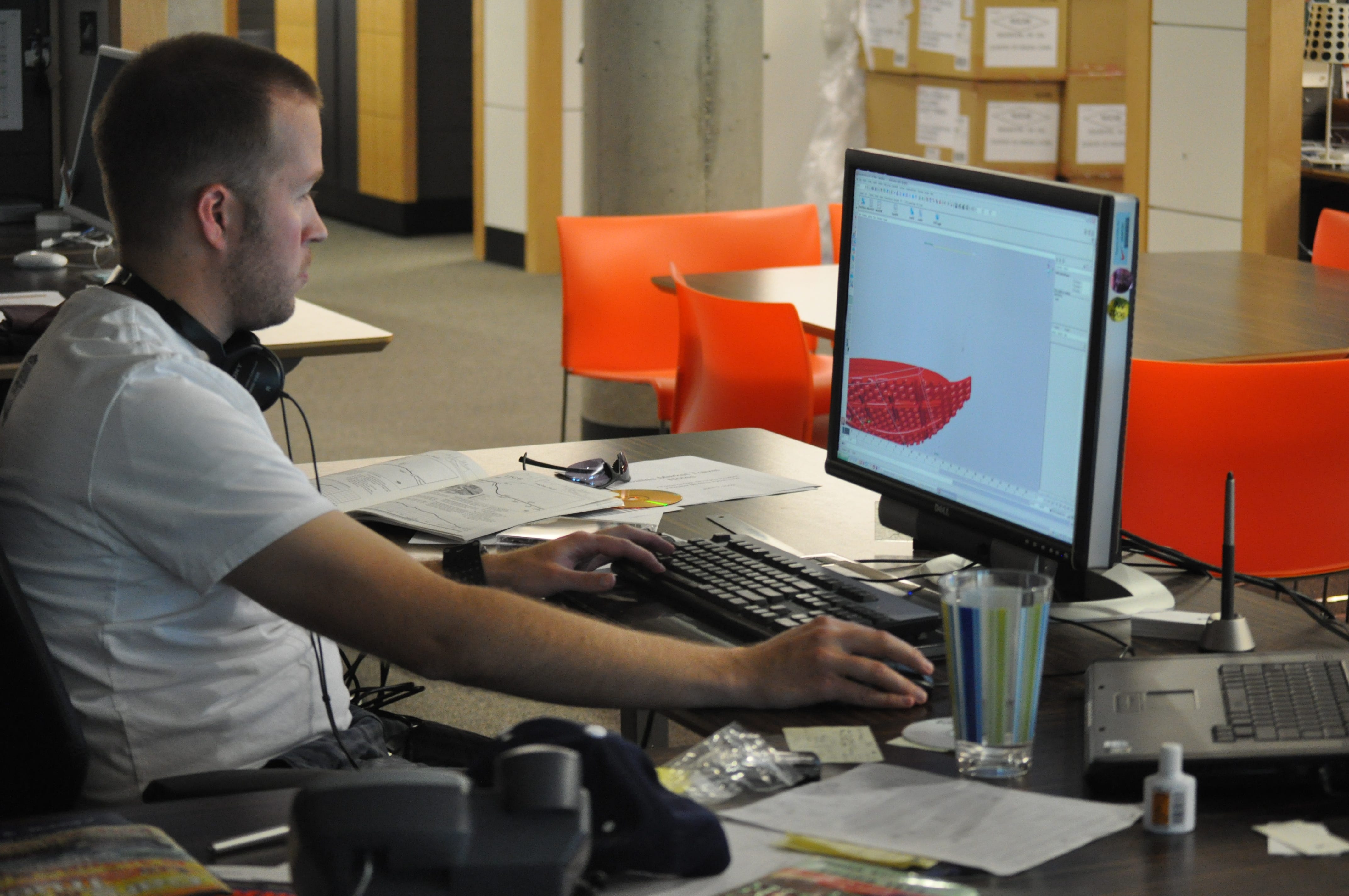

Fast forward to Nike where I landed a job in design and quickly made friends with the resident 3D design guru Jack Wilson. While most of the 3D department at Nike were engineering in ProEngineer, the clunky software developed for manufacturing, Jack was obsessed with Silicon Graphics’ Alias software. If ProEngineer was AutoCAD, Alias was Adobe Illustrator. It made for great visuals and appeared to be the future tool for all designers.

But while Jack was rightfully obsessed, most of the design veterans weren’t even embracing Adobe Illustrator. And as a novice in the sport of design, I had to focus on the accepted tools of creativity to get anyone to take me seriously.

So for a good five years I left the world of 3D alone.

But 3D didn’t die inside the berm without me.

It blossomed, maybe even exploded.

Returning from three years in the Tokyo Design Studio, I found Jack’s obsession was shared by most of Nike’s product creation leadership team. Investment in equipment and software were supported by the push to introduce this technology into every team’s work stream. The expected pushback from veterans was obvious but I understood the possibilities so I rolled with the capabilities.

Unfortunately for me, my workload wasn’t receptive to dusting off my 3D skills. The 3D process was still working out the kinks while our team was tasked with reinventing Nike Running. The process took a back seat to the business.

But somewhere along the way I discovered my real passion for these evolving 3D tools.

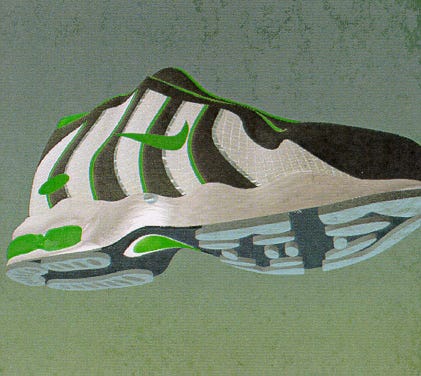

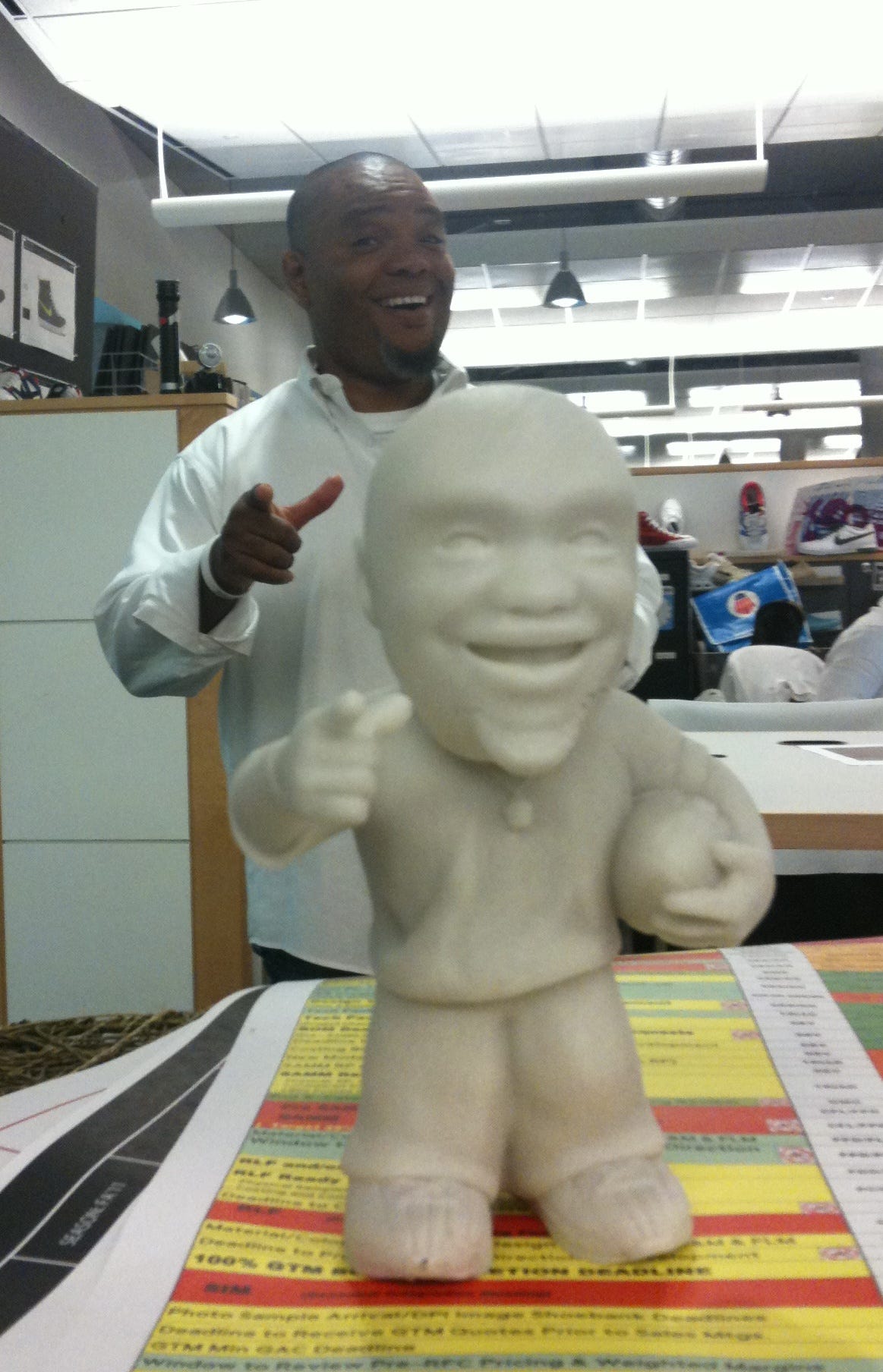

A couple of model makers were using haptic software to sculpt midsole and outsoles in a day. Master craftsmen in clay modeling likeTanya Schroder, Ami Davis and Mike Lombardi could breathe easy — literally — while they applied their skills in a form that could be printed 100 times. Their ability to bring life to every designer’s 2D lies were being left behind because factories were adept at translating Adobe Illustrator drawings into adequate 3D files created by an army in Asia. These new tools allowed Tanya, Ami and Mike to use their modeling skills without sacrificing speed or health.

My connection with this crew went beyond technical need.

My first job at Nike was in their department doing blueprints. R+D Services was the foundational team that supported designers and developers in creating technical blueprints — Tech Packs — to send to Asia. We were the backbone of information that drove product creation.

But as design and factory tools of communication evolved, the need for the 60 person organization shrunk to a dozen individuals that mostly supported veterans that leaned on the service. In 1996 the average designer used their computer as an extra tool. By 2006, most designers saw their computer as irreplaceable in the process.

So I understood that these model makers needed work to keep their job relevant and their eye for seeing details in three dimensions far surpassed us mere mortals. While a footwear designer may work on 12 project a year — maybe 6 that involved new midsole and outsole creation, these model makers had been working on a new project a week for almost 20 years. I trusted their eye of what looked good based on their years of working with talented designers long enough to internalize every eye that Nike brought to their work. They knew how Tinker liked his radius to blend. The knew how Leo Chang liked his sidewalk heights. They knew how Sean McDowell like his outsole lugs spaced. They knew how E Scott Morris liked his sidewalks to bulge.

Their eyes were the best of Nike design eyes.

So I let them work.

I brought our Running design team down to this team and told them to just give them a ‘napkin sketch’ and let them figure out the details.

Of course this frustrated Tanya, Ami and Mike because they were used to getting specific details on every millimeter from designers. But I was okay with looking like I was slacking because I knew that they knew what would look good in the end.

And so did they.

What they had to trust was I wasn’t going to complain about their decisions. They were trained to service the designers and if the designers weren’t pleased, the modelers wouldn’t get work.

But I was one of them. When I said I trusted them, they believed me. And they learned that I wasn’t the only one that leaned on their expertise.

And that’s when I went wild.

As Jack’s obsession turned into Nike’s obsession I found myself in a much larger category — Nike Sportswear. We had far more work to do with less experienced designers. So instead of 8 projects in one year, we had 16 projects in one season. I knew that designers hadn’t exactly embraced the available 3D tools, so I took full advantage of the opportunity for our team. We were printing so many concepts that we decided to print them at 50% to save time.

And that’s when a meeting was called.

The leadership team responsible for implementing 3D tools had a design community that wasn’t fully embracing the future of 3D and one rogue design director that was printing hundreds of dollars per minute. They wanted to spread my enthusiasm and tamper it simultaneously.

Unfortunately I was shipped off to NYC before we fully defined how the process could work for everyone. I assume Nike figured it all out without me. But I lost that resource. I can only imagine how much those 3D ideation models would have helped in other projects.

The expectations of 3D design in footwear hasn’t faded within the industry, but the vision keeps changing with every generation of designers and new tools. I’m curious to see what’s next.

Good things.