Thanks Mike

Three stories.

Are You Stupid or Are You Dumb?

I get to Nike in 1996 with an ounce of design skill. They measure by the ton.

But I landed a job doing blueprints. It was the tedious job of taking a designer’s drawings and turning them into manufacturing blueprints. I was overqualified and bored so I found myself taking on side projects with any one with skill or advice to share.

From Andre Doxey and Aaron Cooper in design to Drew Greer and Steve Riggins in marketing, I had a roster of veterans offering their time and energy without question. I could never repay them for countless hours they spent coaching me. They helped me get my skill level from a 1 to a 7 in no time.

Unfortunately the scale was 1 to 100.

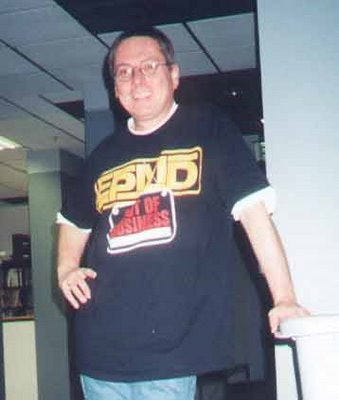

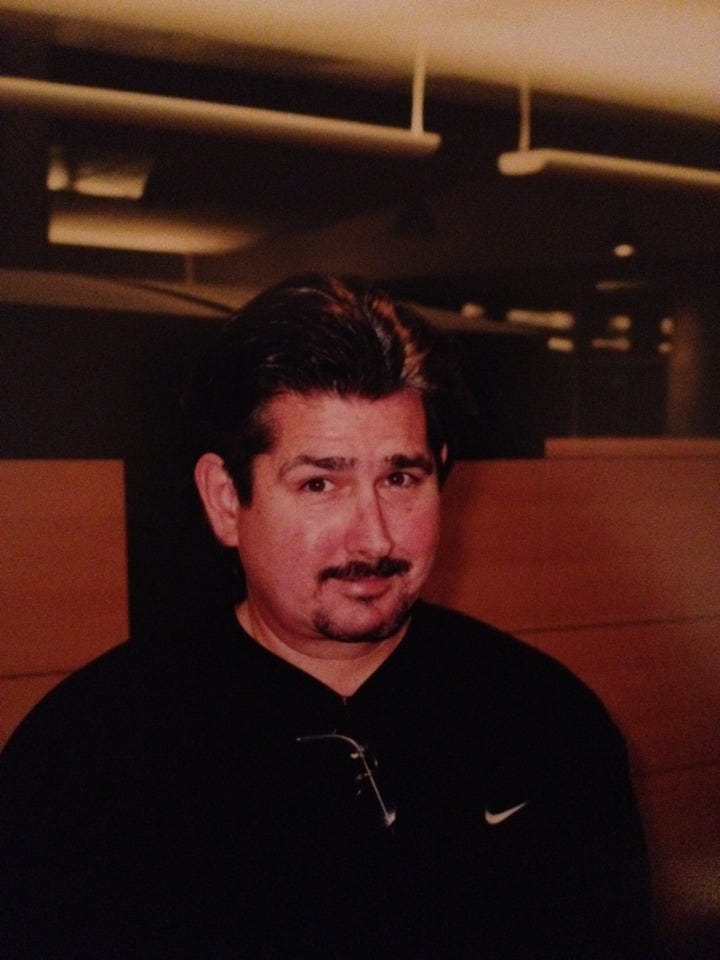

One of my most supportive advocates — by far- was Mike Aveni. By 1996 — when I started — few people knew the quiet guy with the feisty attitude because he’d found a home hidden away in Tinker Hatfield’s group — away from the commercial behemoth focused on the bottom line.

I first met Mike when he brought down a track plate for Michael Johnson -the 200 and 400 meter Olympic gold medalist. Mike’s design was super complex. I was blown away by the engineering involved in the construction as well as the drawing he did in Adobe Illustrator.

At that point most designers were still hand-drawing their ideas, so it was a godsend when we had a digital file we could import directly into our CAD program.

Quickly Mike became my idol.

I hovered around his office more than any other designer as I watched him design the first Team Jordan between flying to Mexico to learn how to make woven huaraches and showing me the Nike catalogs he’d collected for 15 years.

He was one of the original core of designers in the 1980’s. He was practically all of Nike Basketball for a couple of years. Dunk to Flight ‘89. Mike Aveni.

While most designers taught me how to render drawings or how to read a marketing brief, Mike just told me to talk to people and think. He thought like an engineer with a heart.

I was lucky to have people invest their time and energy into my career, so I worked late every night and weekends to get better.

My girlfriend was a saint.

After a solid nine months of learning from a crew of talented and caring creatives, I confidently took my updated portfolio to Sean McConnell, a design manager for the team responsible for creating product for Nike’s best retailers. This was an informal interview to gauge where my talent level was in hopes of landing a job in Nike.

I was prepared for him to make an offer right then and there. I saw what this team was working on and knew that I could execute on that level if I was given the chance.

After a few minutes of flipping through my work, Sean looked up with an authentic face that said I had clearly wasted his time.

But then he did something that no one else had done in the previous six months.

He walks over to his desk and grabs a random stack of portfolios. He drops them in front of me and says, “Go ahead. Open one.”

I pick up the closest book to me and see the most amazing drawing I’d ever seen. My work paled in comparison to what I saw on that page.

“That one’s just okay,” Sean pronounced. “I get a stack of those every week for a job that opens up once a year.”

I was deflated.

“But that doesn’t mean you have to give up,” Sean continued. “Go back to school and develop your skills to this level and you’ll give yourself a chance.”

Sean was right. Most of the designers at Nike went to some school in Pasadena called Art Center. I’d apply there and in two years I’d be a real Nike designer!

Most of my mentors thought this was a solid plan. Art Center was an amazing school and I would get an amazing education.

And then I told Mike.

“School? That’s terrific,” he said excitedly. “But tell me one thing: what are going to study?”

“Industrial design,” I answered.

“Interesting,” he continued. “Another question, if I may: what are you going to design after getting a $60,000 degree?”

“I’m going to design shoes,” I answered.

“Nice,” he replied. “But, wait. What do we design here?”

“Shoes,” I answered.

“Okay. Okay. Let me see if I understand this correctly. You’re going to quit your paying job at a place that designs the best shoes in the world to go to a place that you have pay to learn how to make things that aren’t shoes so you can try to get a job at the place you used to work for so you can design shoes,” he summized. “I guess that leaves me with one more question: are you stupid or are you dumb?”

I wanted to be neither, but in one way or another everyone at Nike supported the idea of me going back to school.

Except for Mike.

And for some reason that was the most logical conversation I had on the subject.

So I doubled-down on my late-nights and weekends until I got into the Kids Footwear Design team 2 months later because Tinker’s team made a push for me.

Bloody Fingers

My job in Nike Kids was the best place for me to start. I spent most of my time taking adult designs and shrinking them into kids designs. I had to learn proportions and costing and consumers, but it was a nice step up from the drafting position I had prior.

The fact that I didn’t have to do many new designs was actually a blessing. Like an apprenticeship, I got to focus on simply execution. On rare occasion I had to ideate on something new, but I was able construct 6–7 shoes per season, which taught me how shoes were really made.

But one day, the Penny 4 that we’d been working on for kids, didn’t get picked up by sales. It was dropped from the line like many of the products we had worked on. My developer, Rich Cawley, was disappointed because he thought the concept would make an excellent baby shoe.

I didn’t have any kids at the time, but I saw how much he believed in it, so I draw up a quick sketch of a shoe with the same construction that Tom Foxen had developed in Innovation — a strap that wrapped around the ankle from the back.

Rich loved the concept, as did everyone else I showed. It was similar to the Air Force 1, because I wanted something that we could sell.

“Do Moms want an Air Force 1,” Mike laughed. “Do babies know what a basketball is.”

Mike challenged me to use the least amount of components to build a simple baby shoe wasn’t made for sales. He told me to make something for mother’s and their babies. And he told me not to draw.

Then handed me some material, a hammer and some nails.

For the last two years Mike had been working on Mexican huarache woven shoes for performance. He spent hours nailing webbing material onto lasts, the hard shoe forms used to build shoes from.

“Drawing is easy,” Mike explained, “but the material doesn’t flow as easy as your pencil. You’ll use less if you build it because it will force you to create the simplest form.”

So I started nailing.

My team thought I was insane. Just as insane as that Mike guy but worse. I was willingly following that Mike guy.

After days of hammering my fingers I landed on a simple design that I thought made sense. My fingers were bruised with a few band-aids where the nails found flesh instead of the last. The 4 pieces of material nailed to the last had a unique shape and an obvious benefit.

I showed Mike and he was impressed. He asked if he could add a nail to tighten the pattern.

As he attempted his first nail he screamed in agony.

It turned out that the baby last were twice as hard as the adult last and because they were smaller they were difficult to handle.

“You did all of these nails on this last?” Mike questioned.

I smiled. It was the first time I saw him impressed.

Six months later that baby shoe would win awards for innovation because the VP of Kids held it up against the best adult shoes in the company and it was just as good.

Two months later my wife and I had our first son.

Still Teaching

After our family returned to Oregon after three years in Japan, we found Mike still working on projects that pushed the envelope. One such project was an idea that centered on unfinished shoes that kids could build themselves. He asked me if I knew of any volunteers that would be interested in trying out his concepts.

I did.

Thanks Mike.

Good things.